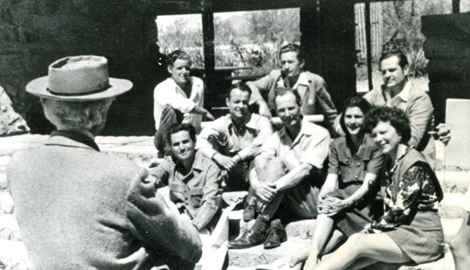

Wright meets with (front row, left to right) Davy Davison, Jack Howe, Peter

Berndtson, Svetlana Wright Peters, Cornelia Brierly, (back row) unidentified, Kenn

Lockhart and William Wesley Peters, circa 1940, at Taliesin West.

Design by Doing

With a daughter, Indira, Brierly lives at Taliesin West, which she helped construct with other apprentices. These included accomplished draftsman Jack Howe; John Lautner, who went on to a distinguished architectural career in California; and Blaine Drake, later her brother-in-law. Brierly’s other daughter, Anna, was named by Frank Lloyd Wright for his mother; Anna lived at Taliesin West for a number of years but now resides in Phoenix.

During those early years and after, she was joined by other female apprentices. John Lautner’s wife, Mary Bud, was there, as was Brierly’s sister, Hulda. And Lucretia Nelson, who later taught at University of California, Los Angeles, and Mary Thomas Thompson, wife of fellow apprentice Don Thompson. “Mr. Wright was a firm believer that the women should do everything the men did, so, in Wisconsin, we worked in the hay field threshing, quarried stone, sifted sand from the Wisconsin River and went out in the snow to cut logs in the forest,” she says, noting not liking lumberwoman duties at all.

Still, she had come to Taliesin because she wanted the experience of hard work, not just the traditional academic studies central to most architectural programs at the time. Brierly had written to Wright in spring 1934, disenchanted with this Old World architectural regimen at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, near her birthplace on a farm in outlying Mifflin Township. He replied by letter: “Come when the spirit moves.”

Moved by that spirit as incorporated in buildings like the Robie House and Unity Temple in Illinois and the Imperial Hotel in Japan, she came, as would succeeding apprentices,

“to Learn by Doing” while also experiencing the fine arts as components of good architecture. “Most American university programs then followed a classical and unimaginative paradigm,” says Victor Sidy, dean of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, the academic component of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, which also owns Taliesin and Taliesin West. “They were importing and extolling the architecture of Europe,” he adds. “But Wright said there was an alternative, an opportunity for a true American architecture, not divorced from life and work. He said, ‘Let’s build buildings that are self-sufficient, nonderivative and representative of the New World spirit.’” Wright was the Emersonian ideal of the American Scholar turned Architect.

Of the 100-plus living Wright apprentices, Brierly is one of the those who remain in Arizona, decades after their desire for an education with him brought them here. Also living at Taliesin West are Arnold Roy, John Rattenbury, Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Heloise Crista, David Dodge, Dr. Joe Rorke and Frances and Stephen Nemtin.

Other apprentices in Arizona are Kamal Amin; Pete ‘Pedro’ Guerrero, Wright’s last photographer, living in Florence, just south of Phoenix; Nick Devenney; Gary Herberger; Tom Olsen, who winters in the Valley; Bill Slatton; architect and community planner Vernon Swaback, FAIA; and writer/urban philosopher Paolo Soleri, who lives and works at Cosanti Foundation, his Paradise Valley school and studio.

“At Taliesin and Taliesin West, you learned about the nature of materials by collecting the materials,” Brierly says, pointing behind her to the concrete-embedded igneous rocks that constitute Taliesin West walls. “We gathered the rocks and the sand from the washes and learned how to put them in forms,” she says, noting that at Taliesin West-hosted reunions, apprentices always proudly point to areas of the building they worked on many years ago.