If there’s a basic truth about life, it’s that breathing is a good thing. Yet Victor Kunisada, now in his 70s, cannot remember a time when breathing was not a problem.

“I had asthma all my life,” he said. “Then, when I was in my 40s, I was diagnosed with COPD.”

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is an umbrella diagnosis that includes a boatload of respiratory and lung problems. “Of course, it didn’t help that I smoked for about 30 years,” Kunisada said.

Respiratory patient Victor Kunisada shows his winning Poker strategy while playing with friend Jeanne McShane. Being diagnosed correctly and getting his myasthenia gravis effectively treated has made retirement recreation a lot easier and much more fun.

“Smoking was a problem,” acknowledged John C. Lincoln neurologist Islam Abujubara, MD. “It was even more of a problem that Mr. Kunisada was misdiagnosed for much of his life. He was treated for COPD, but that was not his only disease.”

As a result, Dr. Abujubara said, the medications and medical procedures that Kunisada received over a 20-plus year span, never solved all his breathing problems. “He was treated with bronchodilators like Theophylline and Albuterol, both of which helped him breathe. But because his true disease was undiagnosed, his breathing problems eventually just got worse.”

Kunisada’s true diagnosis, Dr. Abujubara said, is a neuromuscular disease called myasthenia gravis. “I never heard of that before Dr. Abujubara told me I had it,” Kunisada said. Most people have not.

As in all autoimmune disorders, antibodies interfere with normal body functions. In myasthenia gravis, the antibodies inhibit the signals between the brain and muscles by blocking receptors in the neuromuscular junction where neurons normally stimulate muscle fiber contractions. This causes varying degrees of weakness that increases during periods of activity and improves after periods of rest. Muscles that control eye and eyelid movement, facial expression, chewing, talking, and swallowing are often involved.

Although it only affects 14 to 20 people per 100,000 population, or approximately 36,000 to 60,000 patients in the United States, it is the nation’s most common chronic autoimmune disorder and health experts suspect that, as in Victor Kunisada’s case, it is probably under diagnosed and its prevalence is probably higher.

“I believe Mr. Kunisada’s breathing problems were misdiagnosed for 20 years,” Dr. Abujubara said. “I think the correct diagnosis had been missed because Mr. Kunisada never complained of muscle weakness in his limbs or double vision, which are the two most common symptoms of myasthenia gravis.

Over the years, Kunisada’s wrong diagnosis caused him to be intubated and placed on a ventilator eight different times, Dr. Abujubara said. One of the quirky things about myasthenia gravis is that its symptoms, especially in earlier years of its existence, seem to come and go. Symptoms that can be severe can also resolve themselves for no apparent reason. However, while the course of disease is variable, it is usually progressive. That’s what ultimately brought Kunisada to the Emergency Department at John C. Lincoln North Mountain Hospital.

“My ability to breathe was bad, as always,” Kunisada said, “but then my speech got slurred and I couldn’t swallow. That meant I couldn’t eat. While I was in the hospital, Dr. Abujubara told me that my problems might be more than asthma or COPD. He suspected myasthenia gravis or Lou Gehrig’s disease.”

Lou Gehrig's Disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and the spinal cord. The progressive degeneration of the motor neurons in ALS eventually leads to their death. It is not curable. “When I saw him in the hospital I suspected myasthenia gravis, and I was right,” Dr. Abujubara said. “The fact that he needed to stay on the ventilator for many days many times in the past made me question the strength of his breathing muscles. His symptoms – breathing difficulties, swallowing problems and slurred speech – are all manifestations of myasthenia gravis.”

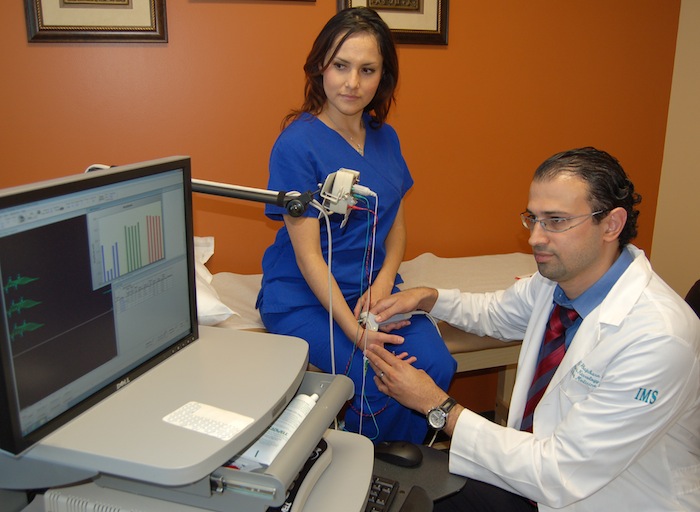

With the help of medical assistant Zulema Hernandez, John C. Lincoln neurologist Islam Abujubara, MD, demonstrates the medical equipment that he used to correctly diagnose Victor Kunisada’s disease, myasthenia gravis. Dr. Abujubara uses the electromyography (EMG) machine to perform a nerve conduction study that tests the ability of the patient’s nerves to electrically transmit messages from the brain to the muscles.

Still, just to be sure, in an effort to get the correct diagnosis for Kunisada’s condition Dr. Abujubara performed neurological testing and blood work looking for the abnormal antibodies. “After the tests were done, Dr. Abujubara came into my hospital room with a huge smile,” Kunisada said. “He said he had good news: I did NOT have Lou Gehrig’s disease.”

Myasthenia gravis was a much less serious problem, Dr. Abujubara said. Unlike ALS, it is treatable. He prescribed medication to suppress the Kunisada’s immune system, to stop his antibodies from attacking. He also prescribed another drug that facilitates transmission in the neuromuscular junction.

“After treatment, Mr. Kunisada got much better and was able to swallow, which meant we could remove his feeding tube,” Dr. Abujubara said. ."I promised Mr. Kunisada that he would be able to swallow again and this made him very happy."

Although Kunisada acknowledges the improvement in his health, he says he has a long way to go before he can return to his youthful activities of playing basketball or softball or bowling in a league.

He does, however, have the energy and stamina to hit the casinos or local poker parlors several times a week to play cards with friends. “I won a couple of hundred dollars yesterday at one of my favorite hangouts, Liz and Rob Ghezzi’s Poker Play in Glendale,” he said, “where they always make a serious effort to watch out for my health. Additionally, I can now swallow and eat. So I’d say things are going fairly well.”

“I think the most significant thing about Mr. Kunisada’s case is that it shows our ability at John C. Lincoln Hospitals to get the right diagnosis for our patients,” Dr. Abujubara said. "Paying attention to the patient’s story and carefully evaluating the medical diagnosis given to each patient to make sure we are not missing another treatable disease is very important and can be lifesaving.”